Bonhoeffer, Trump and a Christian approach to power

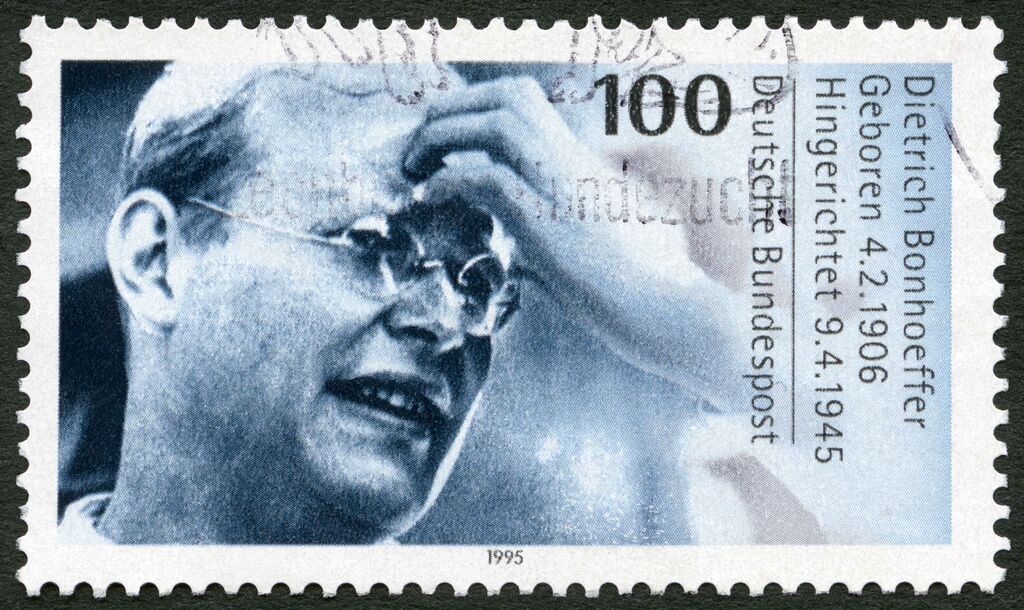

This year marks the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II. A few weeks before Hitler shot himself a German theologian named Dietrich Bonhoeffer was executed. Today sees the nationwide release of a new film, Bonhoeffer, dramatizing his life.

For those less familiar with Bonhoeffer, he was a German Lutheran pastor, theologian, and anti-Nazi dissident. Best known for his staunch opposition to Adolf Hitler's regime and his involvement in efforts to resist Nazi policies, Bonhoeffer was a key figure in the Confessing Church, which opposed the German Christian movement that supported the Nazi ideology.

Bonhoeffer's theological writings emphasized the importance of living out one's faith in practical ways, including standing up against injustice. His writings have resonated over the decades because of their theological insight and because we know that this was a man who lived by what he believed. His lived-out faith led to his arrest in 1945 by the Gestapo, before being executed by hanging in April, just weeks before the end of the war in Europe.

The film perhaps predictably overplays some elements of his life for dramatic effect and skims over other parts of his life and spirituality that were very important to him. Yet I think the life the film depicts is still a poignant counterpoint to how we might be feeling in light of the news from the last week, and the state of geopolitical and domestic politics right now.

It was only last Friday that my wife and I were driving to Wales, listening on the radio to events unfolding in the White House with increasing horror and anxiety. It seems every day brings further unexpected developments, and it can seem as if there is no longer any firm ground to stand on.

And – whatever your option is of the man - this is almost entirely down to Donald Trump.

He is the arch-disrupter, seeking to overturn all the perceived norms for how a Western democratic leader engages international relations, economic affairs, and social issues. Glen Scrivener has described President Trump as “a post-post-Christian leader who resembles a pre-Christian leader.”[1] To be post-Christian is for ‘Christian’ virtues to be cut loose from their Christian, theological roots, and are interpreted subjectively. Post-post-Christian no longer accepts or acknowledges these ‘legacy’ Christian virtues at all – whether linked or not to God. This means that, in Glen’s words, its all about “the deal”. Actions are motivated and governed purely out by self-interest in a world where the strong impose their will on the weak.

If President Trump is indeed post-post-Christian the scenes in the White House last Friday were predictable and inevitable. Zelensky was seeking security assurances; understandable given that the Ukraine has made a number of concessions over the last 30 years in exchange for security guarantees from the US, UK, and other Western nations, only to see Russia take land without apparent consequence. But, right now, Zelensky’s military, economic, and political hand is weaker than Putin’s. Therefore, it looks like President Trump sees Ukraine as the side that must compromise in order to get a deal done.

For President Trump, Ukraine’s legitimate right to its sovereignty and its expectation that past security promises are honoured, stand between him and access to mineral resources for US companies, ‘saving’ billions of dollars in support, and perhaps even a Nobel Peace Prize.

How the scenes in the White House played out last week, and the events since, highlight a very significant difference between the world’s view and the Christian view of power.

I have personally found the Christian author Andy Crouch incredibly helpful in this respect, especially his book Playing God. He sets out the world’s view of power to be much like that described by Friedrich Nietzche. Nietzsche believed that “every specific (individual or institution) strives to become master over all space and extend its force (its will to power) and to thrust back all that resists its extension. But it continually encounters similar efforts on the part of other bodies and ends by coming to an arrangement (“union”) with those of them that are sufficiently related to it: thus, they then conspire together for power. And the process goes on.” (extract from Will to Power)

In other words, so much of the world – including politics – sees every interaction as a zero-sum gain competition. Everything is finite, from natural resources to reputation and influence. There will be a winner and a loser. Even where we think we have achieved a win-win, the reality is that one side is probably being duped into thinking they have a better deal, or it’s a pragmatic truce or stalemate.

But this is not the world God created or wants. It is not the model we are to follow. There is not a finite pool of love and grace, so that the grace I receive is at the expense of my neighbour.

Those who believe in the gospel and that Jesus died as an atoning sacrifice for our sins do not believe redemption and grace is limited. Those of us who believe in the power of the Holy Spirit to open blind eyes and change us over time to be more like our saviour do not think that promise only extends for a limited time or to limited numbers. We do not believe there are quotas on the number allowed into God’s kingdom.

This truth about God should spill over into how we seek to live alongside and to love our neighbour. In God’s economy it is never a zero sum gain competition – rather we see power used for the flourishing of others, and above all, by the Servant King. We are not called to conform to the patterns of this world, or to lord it over others, but to serve them.

In the wilderness Jesus was tempted three times by Satan. All three temptations included some element or promise of worldly power. We are often tempted in the same way. I am concerned that many Christians, whether in the US, the UK or in other nations, give in to this temptation – indeed some seem not to resist it at all and lean into the allure of worldly power.

In God’s economy “power is not the opposite of servanthood. Rather, servanthood is the very purpose of power” (Andy Crouch).[2] I pray that there will be faithful Christians who speak and bear witness to this to the President, as well as to our own Prime Ministers and leaders, wherever they may be.

I am particularly concerned about the way the President and his administration are invoking Jesus or trying to leverage the church to justify or support their actions, positions, and ways of working. In his first term there is strong argument to suggest that President Trump’s excesses were tempered and mitigated by honourable conscientious people – including notable Christians - that surrounded him. Those that surround the President now seem intent to provoke and promote traits that we should condemn.

And this brings me back to Bonhoeffer. His example shows how important it is for followers of Jesus to keep our eyes focused on him as the true source of power and to whom we are ultimately accountable. One of the elements of his story that is perhaps underplayed in the film is the intentional care he took over his own soul and spiritual health. Discernment comes from training and orientating ourselves towards Jesus, and not towards the world and its leaders.

But let us not be brothers and sisters who point to the speck in another’s eye and avoid the plank in our own. Christians in the UK need to be careful who we make alliances with and why. We may not have a Donald Trump as a president, but the temptation of power being offered to Christians and to the church in the UK is very real.

We need many more Bonhoeffers in our nations today. Those ready to speak truth to power. Believers who nurture their own relationship with God in ways that draw on the Holy Spirit’s deep wells of power to resist evil, to act justly, and love mercy. If we fix our eyes on Jesus and not on earthly thrones our eyes will be opened to the things he grieves over.

Bonhoeffer’s story does not have a happy ending in human terms. His story reminds us that often evil often looks like it has won. At times like that we cry out like King David: “why, Lord, do you stand far off? Why do you hide yourself in times of trouble?” But we know that so often, the way to the glory is through suffering, and that the path to the resurrection leads us first to the cross.

We need to pray that our leaders use power as God intended - to serve and seek the flourishing of others before themselves, and not to diminish, destroy, or to pursue selfish gain. We need to pray that their advisers are faithful to God’s better story, with the courage to speak truth to power for the protection of the vulnerable. We need to pray for our own spiritual health, to discern and resist the temptation to seek power for our own benefit.

There may be more days like last Friday ahead of us, but let us pray that we might be the Bonhoeffers wherever God has placed us.