Syria and the human longing for peace

The days are short, the nights are long. We head off to work in darkness and return to more of the same. But as we approach Christmas, we read the great Christmas verses; “the people walking in darkness have seen a great light”.

For while our British winter presents a convenient setting for celebration of the Christmas story, Isaiah speaks of liberation from the bleakness of this weary world, caught up as it is in war, oppression, and pain.

As the passage continues, the great hope of Christmas is not LEDs on a tree, but a child, the harbinger of peace.

Every warrior’s boot used in battle

and every garment rolled in blood

will be destined for burning,

will be fuel for the fire.

For to us a child is born,

to us a son is given,

and the government will be on his shoulders.

And he will be called

Wonderful Counsellor, Mighty God,

Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace.

Of the greatness of his government and peace

there will be no end.

He will reign on David’s throne

and over his kingdom,

establishing and upholding it

with justice and righteousness

from that time on and forever.

The zeal of the Lord Almighty

will accomplish this.

And as Christians gather to celebrate the Prince of Peace, peace once again appears possible in Syria. Just this past week, the Syrian Civil War, which has waged in varying degrees of heat since the Arab Spring of 2011, seems to be drawing to a close.

What has happened in Syria?

After years of bloodshed, oppression, and conflict, this week the Syrian people celebrated the downfall of Bashar al-Assad and the authoritarian regime led by his family for the last 54 years.

Assad’s downfall was sudden and swift. Following the rapid advance of the insurgent group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), breaking out of the North-Western province of Idlib where they had held power for several years, HTS seized the strategic cities of Aleppo and Homs before taking the capital Damascus, prompting the Assad family to flee to Russia.

Even the most powerful men like Assad are but dust to the Lord God. As Psalm 49 states, “man in his pomp will not remain; he is like the beasts that perish.”

Assad’s power, wealth, and brutal reign melted away before him, and one day he will have to give account to his Maker, for the way he used his office to oppress others and not to enact justice.

But in earthly terms, his departure is a remarkable development, given the intransigent nature of his regime, which proved itself to be one of the most brutal governments on earth, responding to the 2011 Arab Spring with ruthless military force against its own people. As the conflict escalated, Assad’s regime broke red-line after red-line, building on years of torture and oppression of dissidents and political opponents by using chemical weapons against his own people.

The Syrian Civil War that emerged became one of the bloodiest conflicts on the planet in the 21st Century, second only to the Second Congo War. More than 12 million people have been displaced, some internally, but many others fleeing to other countries for refuge. This, of course, has had knock-on implications for other nations, and we will be familiar with the intense debate regarding refugees and asylum seekers Europe has been embroiled in for much of the past decade.

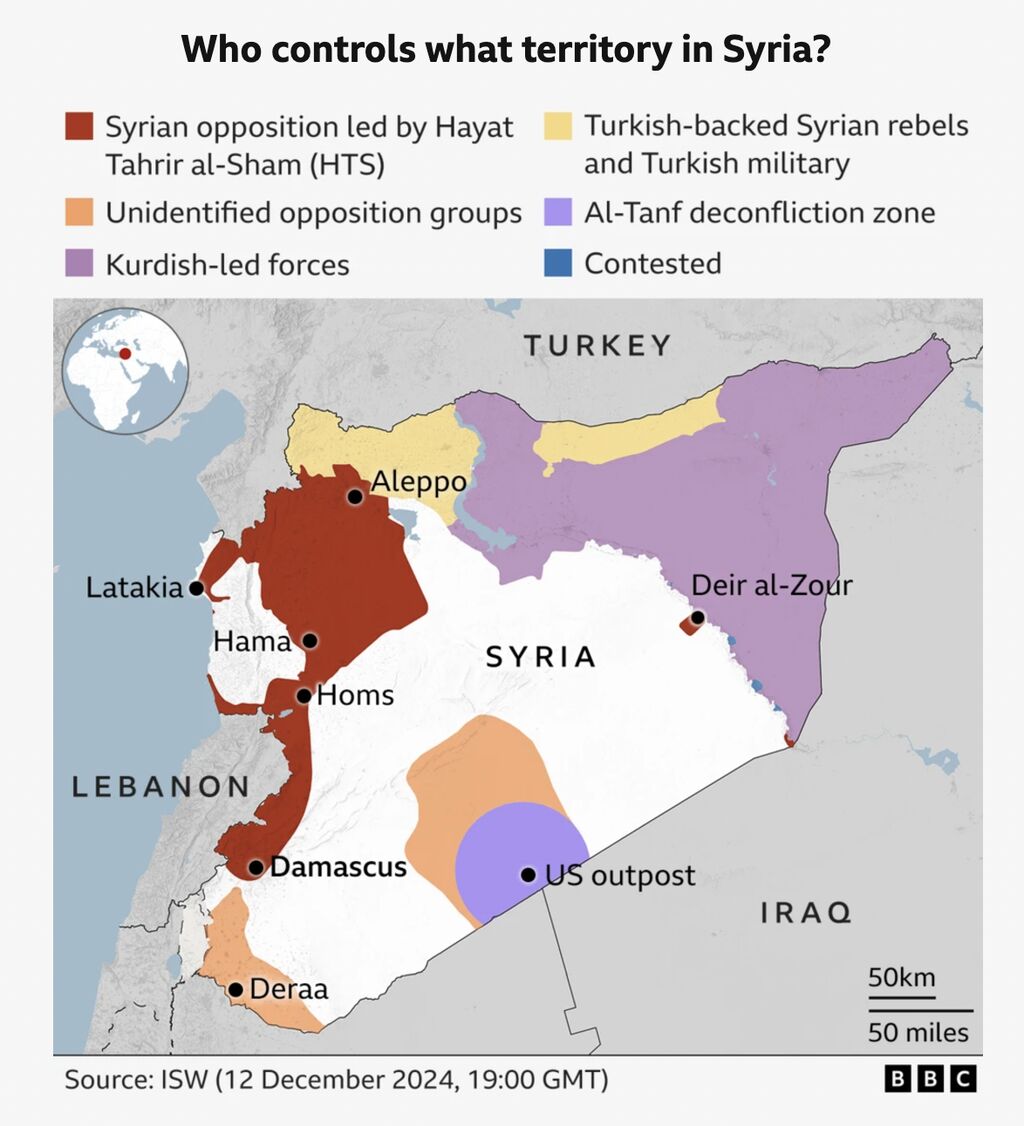

Assad’s control of Syria was far from total, with Kurdish rebel groups backed by the US, Turkish-backed groups such as the Syrian National Army, and Islamist militants such as ISIS all controlling vast swathes of territory at differing points and to varying degrees over the course of the 13-year conflict.

Assad’s own hold over the country was only sustained through significant military intervention by both Russia and Iran (and Iranian-backed groups such as Hezbollah). Seemingly too pre-occupied with their own geopolitical crises in Ukraine and Lebanon/Gaza respectively, neither Russia nor Iran proved able to stem the latest assault, and so the regime, which had been dominant and iron-fisted for so long, crumbled away like dust in the breeze.

As HTS moved into the capital, the world’s attention was once again turned back to the horrific abuses of the Assad regime. Particularly harrowing have been the accounts of the notorious Sednaya Prison, known as a ‘human slaughterhouse’. Families flocked to the prison in search of loved ones who had disappeared. The fortunate ones found their loved ones alive, though by no means well. Many many more were distraught to learn it was too late, their family and friends having been tortured, killed, and discarded.

A complicated situation

It is therefore unsurprising that much of the coverage of Assad’s downfall has focussed on the seemingly widespread euphoria of the Syrian people and the palpable sense of anticipation in the country that a better future might be possible.

Given the number of international powers with some level of involvement in Syria (Turkey, US, Iran, Russia, Israel, to name just the main players) there are significant international repercussions too. For Turkey, this potentially spells the dawn of a new era of influence in the region, with Erdogan’s government holding influence with HTS as well the Syrian National Army.

For Iran, Assad’s downfall will likely disrupt their ability to supply their proxies in the region and see them deprived of a key ally. For Russia, their inability (or unwillingness) to prop up the Assad regime for any longer seems to demonstrate their military weakness and could potentially see them deprived of their naval and air force bases in the nation (though they retain control of them for now), which would in turn see their ability to project hard power in the Middle East and Africa much reduced.

Israel has moved quickly to strike at Syrian military hardware and, if you follow the party line, reduce the likelihood of military equipment falling into the wrong hands. Either way, they will take great comfort from the downfall of an Iranian ally on their northern border, and the limitations this will have for other Iranian proxies in the region.

Sadly however, both current events and history in the region suggests that this is likely to be a far more complicated and morally ambiguous development than we might like to believe. After all, the initial protests of the Arab Spring sparked hopes and dreams of a democratic and free Middle East and yet within months had descended into a murderous bloodbath.

Whilst initial reports from Syria are focussing on newfound freedoms and accompanying celebrations, HTS themselves are an Islamist Militant group with historic ties to al-Qaeda and ISIS. Much has been made of their efforts to rebrand in recent years, and they have been deemed pragmatic by many commentators, but it remains to be seen whether they are a truly reformed outfit that will guarantee the freedoms and security of minorities. It is not uncommon for those hailed as liberators to descend into the barbarism they once denounced.

And this is not a stable region, as this map produced by the BBC shows.

Syria is not a coherent whole, but a land carved up by different factions and international interests, often with seemingly incompatible goals and aims. Take for instance, the virulent animosity between the Turkish-backed groups in the north and west, and the US-backed Kurdish groups in the north east. Furthermore, with Israel moving in to occupy the Golan Heights, in the south west of the country, there is every chance that this conflict rumbles on with no clear end in sight, causing further suffering and destruction for the Syrian people and the wider region.

The universal longing for peace

Peace, of course, is the great hope, and the celebratory response of many of the Syrian people this week chimes with the longing for peace, encapsulated in the Christmas story. Christmas reminds us of the coming King who is the Prince of Peace.

The clamouring for peace is one of the deepest longings of the human experience, and the absence of peace, one of the surest signs that this world is not as it should be. Yet the Christmas story is also a reminder that for all we ought to work towards peace, the best we can hope for this side of the veil is a temporary and bit part peace.

For the peace that Christmas points to is an ultimate peace, complete and comprehensive, in which evil holds no sway, and all injustice and oppression has ceased. It is not a peace that can simply be brought about by us humans.

Recent decades have offered very little hope that we can bring about peace through our own efforts and means. Consider just the 21st Century, and the efforts to bring peace and stability to Iraq and Afghanistan. Our attempts to intervene on behalf of democracy have achieved little. We can certainly do good, but we cannot put an end to the wretched nature of humankind to descend into violence and bloodshed.

This should not necessarily be a cause of despair; rather it should foster a healthy realism about the nature of the world as it is, and our limitations within it.

There has been much less clamour this week for Western intervention than in recent years; in some cases, as the words of the future US President attest, there is a reluctance to get involved at all.

There may be wisdom in this, acknowledging the complexities of geopolitical realities, the limitations of our ability, and questioning whether intervention will actually help (for all that it might be well-intentioned).

Yet, if this world is all there is, it is, ultimately, a pretty bleak picture.

It is the message of Christmas that ought to give us hope. For the people walking in darkness have seen a great light; the hope promised to Israel back in Isaiah 9 is a hope not just for the Jews but for the whole world.

For all that it is hard to see which direction the Syrian conflict may now go, our longing for peace points us towards a sure and certain future, in which the Lord “will judge between the nations and will settle disputes for many peoples. They will beat their swords into ploughshares and their spears into pruning hooks. Nation will not take up sword against nation, nor will they train for war anymore.”