Can you remember your first mobile phone? I can remember mine. It was a blue Siemens C25e and the fact that you could choose from a range of ring tones was the main feature that put it head and shoulders above the rest … or so I was told at the time. I could ring or text friends and family confident in the knowledge that when they rang me I could tell who was calling simply from the ringtone. But I couldn’t download email. Neither could I tweet, seek directions from Google maps, book my rail e-tickets or ask Siri. Strange as it may seem compared to today’s standards it really was just a phone!

How digital technology has evolved over the decades is amazing to witness and be a part of. Two key factors have helped drive this revolution. First, the chip; not the type you can eat but the small, silicon variety. As these chips have become smaller and cheaper to produce, so have the computers which they help to power. Second, the advent of the internet has ushered us into a world of digital interconnectedness. Whilst the internet was the brainchild of Vint Cerf and Robert Kahn, it was Tim Berners-Lee who took their invention and increased its usefulness by developing the worldwide web. Just think about the following facts: It took radio, 38 years to attract its first 50 million listeners. It took TV 13 years to attract its first 50 million viewers. But it took the ubiquitous worldwide web just 4 years to attract its first 50 million users.

Consumers now spend on average more than five hours a day on their smartphones, and a recent AdWeek survey found 88% growth year over year in time spent watching videos on a smartphone. It sounds incredible that worldwide, more people own a mobile than a toothbrush and that the number of mobile devices that exist in the world already exceeds the world’s population.

With smaller and more powerful computers and the connectedness of the web, the digital revolution has seemingly turned our world upside down ... but to quote the well known phrase You ain’t seen nothing yet! There is every reason to believe that the technology is going to get faster and faster which only helps to emphasise that the challenges we face in making the best use of it, are only going to intensify.

We could consider these challenges as coalescing around two main areas: relationships and responsibilities.

Relationships

We are creatures who have relationships – human relationships, personal relationships – just as God has a relationship with us. Advances in digital technology are helping us to stay connected and communicate in more convenient and easier ways. At the same time, as we adapt and incorporate these new technologies into our lives they threaten to strip away important aspects of how we relate and connect on a personal level. US Research conducted in 2014 by Pew Research Center poll indicated that one in four mobile owners in a relationship or marriage found their partner too distracted by their cell phone. Nearly 1 in 10 had argued with a partner about excessive time spent on the devices.

Deloitte conducted a survey in 2017 of 4,150 British adults about their mobile habits. 38% said they thought they were using their smartphone too much. Among 16- to 24-year-olds, that rose to more than half. Habits such as checking apps in the hour before they go to sleep (79% of us do this, according to the study) or within 15 minutes of waking up (55%) may be taking their toll on the health of relationships.

A recent study from the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine examined depression rates in younger adults, finding significantly increased odds of depression among those spending the most time engaged in social media. The study also notes that further multiples studies indicate a link between social media use with declines in mood, sense of well-being, and life satisfaction. In turn, the phenomena of FOMO (Fear Of Missing Out) could be shaped by these declines which are have been shown to be often exacerbated by social media use, resulting in poor mental health.

There is certainly a convenience to digital communications but the impact of time spent in front of a screen has the potential to lead to adverse consequences for what it means to be human and our lived day to day lived experiences.

Responsibilities

Greater access to technology has reduced the digital divide, but the transformation in digital platforms from Web 1.0 (passive receiver of information) to Web 2.0 (user generated content, interoperability, collaboration) has opened up what has been called the digital literacy divide. A person’s digital literacy skills will help to determine their capacity to experience that greater level of autonomy, personal insight and understanding of many different life issues. This can range from the very personal (relationships and health) to the very public of sharing views and opinions on the latest top issue. As many of us will realise, this poses exciting possibilities for the future as well as matters of great concern. The mobile device and its growing capability power represent the democratisation of so many aspects of life in a way we have yet to understand or express.

As Christians, what ever else being made 'in God’s image' may mean, it enables us to serve as His stewards in managing the earth, which involves the development of science and technology. There is a need for us to demonstrate our responsibility in order to see technology harnessed for the benefit of all of humanity.

Where do we start?

Looking at the life of Jesus we don’t read about him texting his disciples to arrange a discipleship meeting or taking a photo of his latest miracle and putting it on Instagram. Just what would Jesus do in a digital world? Flicking through a concordance there are no references to mobile phone, microchip, GPS or artificial intelligence. So where do we start?

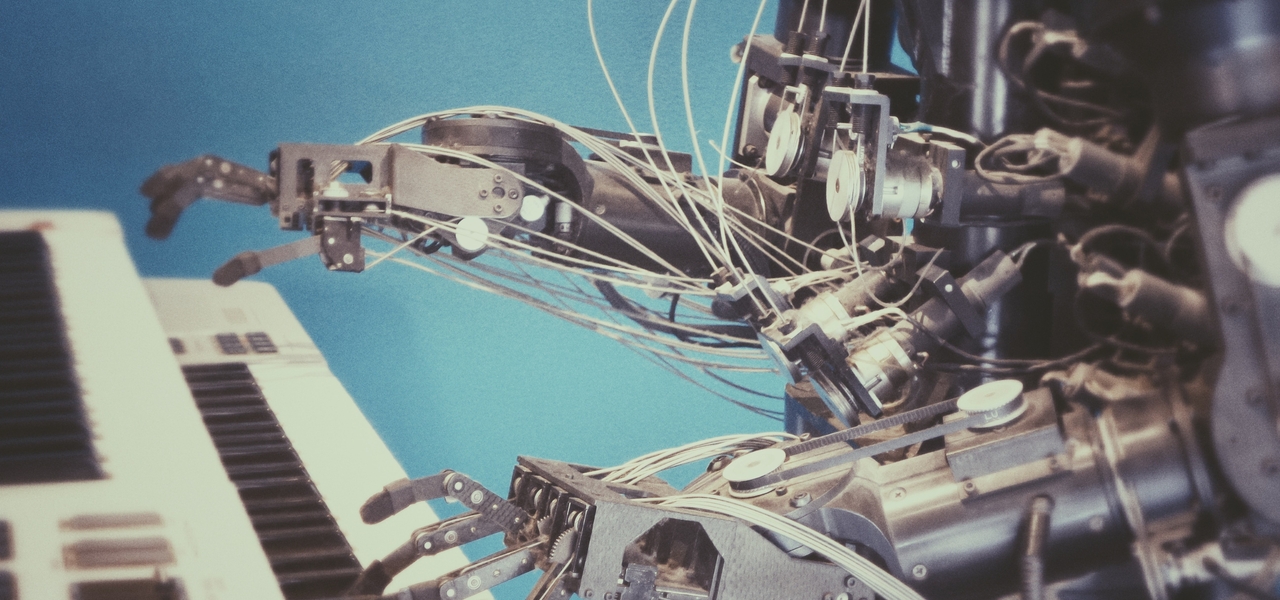

First, as our focus is increasingly drawn to consider the interaction between what is human and artificial, we begin to cut straight to a core question which underpins the Christian faith: what does it mean to be human? We need to remember that we are not only Homo sapiens or ‘wise man’ but also Homo faber - ‘working man’ and later manufacturing or creative man. The whole idea of technology, from the most primitive tool to the latest silicon chip, is the story of us making things that enable us to do more than we could do without them. As theologian Prof Brent Waters has commented “technology is the way we live and move and have our being in today’s age”. It is through technology that we increasingly express who we are and what we aspire to become.

But in fulfilling our creation mandate to take dominion and work the land (Genesis 1:26-31) we need to be wise that we do not end up becoming slaves to the very technology that is supposed to be serving us! It was this recognition that drove C.S. Lewis, in his prophetic essay of 1943, The Abolition of Man, to argue that while technology is said to extend the power of the human race, “what we call Man’s power over Nature turns out to be a power exercised by some men over other men with Nature as its instrument.”

You only have to consider the statistics offered above and reflect on the public debate concerning how social media companies harvest personal data to drive and provide their ‘free’ services, to realise how these power dynamics can play out today.

Reaching a tipping point?

If the digital revolution has only just got started, what is to our response and can we really expect to make a difference?

Author and public speaker, Malcolm Gladwell helped to popularise the term ‘tipping point’ as that seemingly magical moment when ideas and trends reach a certain point and spread like wildfire. This has a certain resonance with what we read in Matthew 13:33 where Jesus talks about the Kingdom of Heaven being like yeast in the making of bread. Only a little yeast may be used but it spreads and permeates every part of the dough.

What lessons can we learn from this as the digital revolution develops? How can we achieve a tipping point that goes beyond just a deluge of new tech to one which ushers in a revolution that helps humanity to flourish through the use of digital technology? As Christians how can we play our part in this?

In his book Gladwell identifies three key factors that help to achieve a tipping point:

1. The law of the few

2. The stickiness factor

3. The power of context

1. The law of the few

The ‘law of the few’ refers to “the success of any kind of social epidemic is heavily dependent on the involvement of people with a particular and rare set of social gifts" (Malcolm Gladwell, 'The Tipping Point'. This kind of thinking is reflecting in what economists refer to as the 80/20 principle: in any given situation roughly 80 percent of the 'work' will be done by 20 percent of the participants.

So what relevance does this have to digital revolution? In this wonderful new world of connectedness, the Internet provides us with amazing access to vast amounts of knowledge. Undoubtedly this does help us to access information in order to keep informed on issues and to allow us to think for ourselves as to what our response might be. At the same time, this quick and easy access to information also means we have unparalleled exposure to a vast array of opinion and perspectives on practically every topic under the sun. From public affairs to parenting; from clothes to pet choice, there is always someone out there who is more than willing to share their views. This means it is a lot easier for people to believe things that are downright bizarre that they would otherwise recognize as not being likely to be true.

Many of us mostly settle down into an online life that best suits us . We recognize our particular take on life, hobbies, interests and currents affairs and we settle down into the online life that keeps us within our comfort zone. Our ‘filter bubble’ helps to filter out facts and opinions we don’t like.

This new digital revolution is empowering us to gain understanding and perspective on many different issues and yet at the same time, it facilitates those who have more extreme and odd views to make their voice heard and share their ideas. When we weren’t able to so easily connect with people in the same country, let alone in a different part of the world, it wasn’t so easy to gather support and build momentum for their ideas. The digital revolution is helping to respond to this by bringing people ‘together’ in a new way and to build support around ideas. To use Gladwell’s words: we can create a tipping point for their ideas.

But ideas spreading like wildfire says nothing about the authenticity and reliability of the ideas being shared.

We have to remember that experts can get it wrong. Just think back to the time before Copernicus and Galileo. The established scientific community held the view every bit as strongly as the religious community that Earth was the centre of the universe, around which the sun and other planets revolved. Copernicus and Galileo challenged this idea with their ground-breaking and radical proposal that Earth actually revolved around the sun.

This doesn’t mean we should disregard science in the belief that it will be likely proved wrong or even dismiss entirely the value that scientific knowledge and explanation can bring to understanding everyday life. It calls for us to appreciate the nature of how scientific knowledge can advance and develop. As argued by Thomas Kuhn, physicist-turned-philosopher and historian of science, we can be sure it is likely to look very different in future to how it looks now.

With this in mind it is important to remember that as with so many aspects of life, the internet’s greatest strength can be its greatest weakness. The ease at which new ideas and information can be shared and broadcast around the world means that it is an equally efficient generator and disseminator of ideas and perspectives, which have little grounding in fact or truth. Cue the emergence of ‘fake news’.

The challenge is to be found in deciding how best to think for ourselves and yet not fall prey to the latest charlatan ‘tale’. A basic, yet practical approach is to disagree with what almost everyone thinks so you can find a group of people who are ‘experts’ who equally agree with you. It needs to be more than you and your dog but equally it doesn’t have to be many. But a few. As Nigel Cameron comments:

“I know very little about cancer or vaccine, but I do know that unless a bunch of people who know an awful lot about these things are prepared to put their reputations on the line, it’s ridiculous for me to disagree with the wisdom of the scientific community. Of course, if I am an ‘expert’, it’s a different question. But unless I am, I’m either a charlatan myself or following the charlatan who has dared to challenge everybody else.” (Nigel Cameron, 'God and my mobile')

In this era of the digital revolution, we can see how the law of the few can be applied to explain the ease by which people can share their ideas and gather support for them. There is equally a lesson here for Christians to develop an enquiring mind. Not a mind that is deeply suspicious of anything new but is open to learn and question.

It is timely to remember the apostle Paul’s words in Romans 12:2 – “Do not conform to the pattern of this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your mind. Then you will be able to test and approve what God’s will is—his good, pleasing and perfect will”. Note Paul said by the renewing of your mind, not its removal. Our mind, understanding and reasoning is important to God and we need to use it, listening to and paying close attention to the Word of God, humbly submitting to its guidance and instruction as we grow as believers. At the same time, yet in a different way, we are to as John Stott urged us, to ‘double listen’ – “listen to the world with critical alertness, anxious to understand it too, and resolved not necessarily to believe and obey it, but to sympathise with it and to seek grace to discover how the gospel relates to it” (John Stott, 'The Contemporary Christian').

Jesus made almost an art form out of asking questions in order to help his listeners uncover meaning and understanding. Questions have been described as “…merely launching pads for further exploration, places to prepare for the creation of new and more insightful questions” (C.R. Christensen, D.A. Garvin, A. Sweet (ed), 'Education for Judgement'). Could it be that as we double listen and engage in the art of asking questions of the digital revolution, we might find some new perspectives and ideas to help answer the tough questions of today and tomorrow?

If the law of the few speaks of how just a handful of people can add advance news ideas, then surely this same ‘law’ also provokes Christians to not cower in the corner, but play their part in helping to question and critique ideas being advanced so as to see the digital revolution as a force for good in humanity’s flourishing.

2. The stickiness factor

The stickiness factor helps to identify and describe the quality that compels people to pay close, sustained attention to a product, concept, or idea. One example from his book describes a research project conducted in the 1960s on the campus of Yale University which explored the importance of fear in learning. Two groups were set up; one was given a booklet about the importance of tetanus inoculation, whilst the other was given a booklet about the serious dangers of getting tetanus. Those from group B were found to be more much likely to say that they would have a tetanus jab, yet the rate of follow through was pretty low. They appeared to know the information but didn’t appear to act on it. The research team tried the experiment again but with one significant change. A handout was given out to both groups which included a campus map with the university health centre clearly marked and the times when students could come and get inoculated. The result was that more students followed through on actually getting a tetanus jab. What was needed was not more information but rather how the information related to them and their lives. Once the information became practical and personal, it became memorable. The message stuck.

Looking at the effects of the digital revolution it appears that it is inherently ‘sticky’. On average, research indicates that in the UK 38 million adults access the internet every day and internet users aged 16 and over spends more than 20 hours online each week. Digital technology is compelling us to pay close, sustained attention to our mobile devices in so many different ways. Whether it’s Facebook, Instagram, Twitter or any other of the many platforms and apps available, there seems a plethora of options from which to choose from in order to stay connected and keep our nearest and dearest informed of what we’re up to and our current thoughts on life and the universe. It’s practical, personal and memorable. What’s not to love?

Despite our use of the term ‘social media’ to describe these platforms, at times they can be anything but social environments. They have given us the freedom to literally express ourselves, no holds barred. Whether it’s lies and fake news or internet trolling and social disinhibition, far from being a liberating experience social media has led to new social phenomena that doesn’t exactly show humanity as its best. A study conducted by the world renowned Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) looked at 126,000 messages spreading false stories on Twitter. They concluded that the truth takes six times longer than fake news to be seen by 1,500 people on Twitter.

These platform also appear to give us freedom to behave in ways that we would never think of if we were meeting them face-to-face. Bullying and insulting others through social media, often referred to as trolling, is a product of this new found social disinhibition. Social media provides a very real and valuable opportunity to engage and exchange points of view with one another, enriching dialogue and understanding. Yet there are those who passionately argue their case at the same time as denying the same right to those who hold to contrasting or conflicting perspectives. Sadly the words of French Enlightenment writer Voltaire seem to be largely ignored when it comes to our use of social media: "I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it”.

It appears the ‘stickiness’ of digital technology compels us to engage, but at times with serious consequences on the rest of our lives and what it means to be human. In recent years much has been written about the use of technology and mental health. Despite our apparent connectedness online studies have consistently shown that one in 10 of us is lonely and a report by the Mental Health Foundation suggests loneliness among young people is increasing. Yes, digital technology can help to reduce social isolation but research indicates cognitive function improves if a relationship is actual rather than virtual and involves ‘old school’ face-to-face interactions. There is something inherently different between a Facebook ‘friend’ or a Twitter ‘follower’ and a real, human friend.

Ridding our lives completely of all digital technology may be one response but it would be largely impossible, such is the impact of technological change on how we live our lives. Taking time to re-assess what we do with our time may be a better starting place. The stickiness of the online, connected lifestyle and extreme compulsion to sustained engagement has led to what is now known as internet addiction (now a recognised mental condition in the US and other countries). Higher rates of depression and anxiety, and lower measures of self-directedness and cooperativeness have all been attributed to this kind of addiction.

The word ‘addict’ originates from the Latin term “addictus”, used to denote the time served by indentured slaves. In the ancient world, the addict was the slave. In today’s digital world, we must make the decision who is to be the master and who is the slave. Our mental health and what it means to be human could well depend on it.

In his book, Gladwell addresses the stickiness of the attention grabbing techniques used by the pioneers behind the hit children’s TV series, Sesame Street. The show was built around the idea that by capturing the children’s attention, you could then begin the process of educating them in reading, writing and maths. Essentially, the children came for the stickiness and stayed for the education. In a similar way, the challenge seems to be to harness the stickiness of the digital revolution to sustain connection and contact with one another by helping to augment our human, relational interactions as opposed to replacing them.

Given the current state of affairs with trolling, loneliness and social disinhibition, maybe the stickiness of the digital world could help people to connect and then educate how best to engage and relate to one another before encouraging them to go experiment with 'old school' biometrics: meeting and relating face to face. To quote John Naisbitt as our desire for 'high tech' increases, there is an equally growing need for 'high touch'. Bringing the two together is what truly makes a personal, practical and memorable experience.

3. The power of context

Put simply, the power of context is recognising the fact that humans are sensitive to and strongly influenced by the environment in which they live. In ways that we don’t necessarily appreciate, our inner states are very often the results of our outer circumstances. The outward affects the inward. That is not to dismiss the importance of personality and psychology and the part they play in shaping behaviour, but there are particular points in time when context can tip human behaviour in a certain direction, regardless of personality.

Gladwell believes social phenomena act as epidemics, which are, at their root, all about the process of transformation. The digital revolution could be regarded as an epidemic as it transforms our lives in unprecedented ways. If we are to keep the faith in the digital revolution, we can our play our part in helping to question and critique ideas being advanced so as to see the digital revolution as a force for good in humanity’s flourishing. As we’ve seen, that’s the Law of the Few in action.

Changing the content of communication can do it; by making a message so memorable that it sticks in someone’s mind and compels them to action. That’s the Stickiness factor.

We have seen how the effects of the digital revolution are inherently ‘sticky’ leading to many positive as well as negative social implications. In response there is a need for us to make the message even stickier by demonstrating the importance of creating a ‘high tech, high touch’ world.

Small changes in our context though can be equally as important which can be found in the power of context. During the 18th – 19th century the Methodist movement became an ‘epidemic' in England and North America, tipping from 20,000 to 90,000 followers in the space of five or 6 years in the 1780s. By no means the most charismatic preacher or theologian of this era (those accolades could be awarded to George Whitfield, Calvin or Luther), John Wesley’s genius lay in his ability to organise.

In each town he visited, he stayed long enough to establish groups of his most enthusiastic of this converts. Converts were required to commit to attend weekly gatherings and to adhere to a strict code of conduct. The consequences of them failing to live up to these standards were expulsion from the group. These groups therefore stood for something and built a sense of community with clear boundaries.

Wesley realized that if you wanted to bring about a fundamental change in people’s belief and behaviour, a change that would persist and serve as an example to others, you needed to create a community around them, where those new beliefs could be expressed, shared and nurtured.

No trend can “flourish” without the right context. As we have seen the digital revolution brings with it many opportunities and benefits, but how far should we pursue these? The convenience by which we can ‘connect' and interact, confounding the barriers of time and space, is amazing but what is it doing to maximise the human experience? Observing the rise of internet trolling, social disinhibition and increased levels of loneliness would suggest some real areas of concern.

Rather than fearing the digital revolution, the Church is well placed to help demonstrate and maximise the benefits of the digital revolution. In community we can help and support one another live out a life that champions both the 'high tech' and 'high touch’.

The fundamental question facing the human race is whether the twenty-first century will be the century during which technology rules the roost, or humans rule the technology – and use it to advance all those things that are good for people. If it’s to be the former, we need to remember C.S. Lewis’ sobering words from way back in the middle of the last century. That when we talk about our ‘conquest of nature’ (that is, technology) what’s really going on is that some people use ‘nature’ to exercise power over other people.

If culture is the glue that holds society together, or the beliefs, behaviours, attitudes and values of a particular people group, then the Kingdom of God is his alternative culture that his church is building. The Church is called to challenge the assumptions of the culture, called to speak prophetically into the public arena. God is raising up a church that will work in the arts, media, politics, business, law and order, health and education to establish His culture - the Kingdom of God.

As the Church we believe relationships to be central to what it means to be human, taking time for each other and with each other. Yet also we are supposed to be the ones who believe that God created the heavens and the earth and then gave to His human creatures a special responsibility to manage and develop His creation. What theologians call the cultural mandate. Responsibility for science and agriculture and the arts and government and every other dimension of life on the planet. That’s ours, and it means we will never be right if we turn against new knowledge and pretend it isn’t there. Yet at the same time as we embrace knowledge and learning and all that goes with the new technologies, we embrace them as stewards. With responsibility. As Nigel Cameron notes, "We’ve got God’s garden to take care of. But it’s God’s garden."

Proverbs 29:18 states, "Where there is no vision, the people perish". This is a popular text, more often associated with setting goals for our lives. Taking a deeper look at this verse and reading it an alternative translation, helps to illuminate the text still further. The Hebrew text says: “Without a redemptive revelation the people lead undisciplined lives.” This verse talks about you and me redefining the culture of our immediate environment.

God wants to inspire us not just with a sense of purpose and set of goals for our lives, but a redemptive revelation of Himself. He wants to show you something of his own nature; something so revolutionary that, if you live it out, it will actually redeem things around you for the kingdom of God. Because of that revelation, you will be able redefine what it means to be human and to make sense of how to do life within the fascinating digital era in which we find ourselves in.

We can’t run away from our responsibility to help lead the ethical discussion any more than we can get out of commitment to embrace new science and technology. The contemporary Church has an exciting role to play in helping to challenge the conventional wisdom, to commit ourselves to thinking hard and doing the right thing, and then begin to exercise the kind of leadership that former generations of believers did on the great issues of their time. It’s time for Christians to respond to the call to be distinctive, and to be smart.

The tech revolution has changed everything and poses a fundamental question for us to respond to. Will the twenty-first century be the century technology becomes king by ultimately ruling over us and control our lives? Or will it be the century when humans use their God-given stewardship over the natural order to bring about peace and prosperity and the flourishing of our human-ness – a human-ness made in the image of God? There’s a tipping point on the horizon.

Matt James is the Director of BioCentre, a think-tank specialising in Christian ethics and emerging technologies.