“I believe passionately that any individual should have the right to choose, as far as it is possible, the time and the conditions of their death. I think it’s time we learned to be as good at dying as we are at living.”

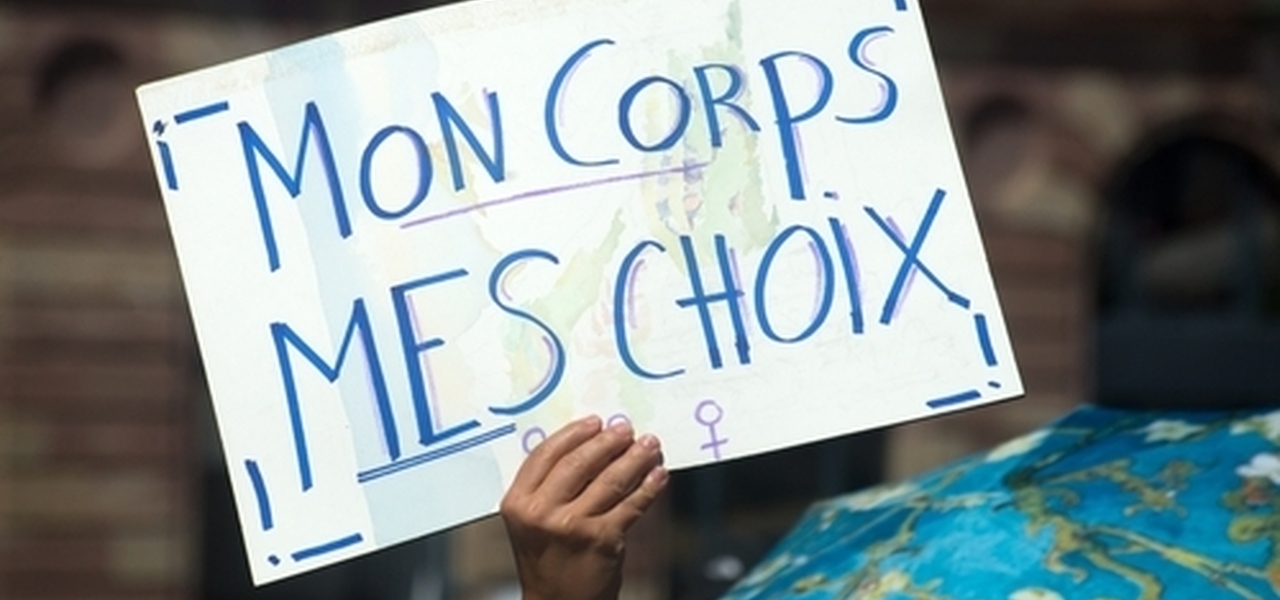

On the surface it seems so simple. Human beings have the right to choose – end of story. If we can control every other aspect of our lives, such as where we live, how we spend our money, how we spend our time, then why on earth cannot we choose how and when we end our own lives?

Philosophers call this the principle of autonomy, a word derived from the Greek auto-nomos, meaning self-rule, or more crudely, ‘I make my own laws’. Autonomy is the principle behind patient choice. It is enshrined in the Patient Charter, the NHS Constitution, the Mental Capacity Act and in General Medical Council guidelines for doctors. It is the patient who should be at the centre, choosing and controlling what treatment should be given. And given that we have the right to make choices about every other aspect of our medical treatment, why do we not have the right of self-rule when it comes to when and how we die?

Here’s philosopher AC Grayling: “I believe that decisions about the timing and manner of death belong to the individual as a human right. I believe it is wrong to withhold medical methods of terminating life painlessly and swiftly when an individual has a rational and clear-minded sustained wish to end his or her life.”

There is no doubt that respect for individual autonomy is a fundamental principle of modern medical and legal practice. English judges have repeatedly ruled that patients with legal capacity have an absolute right to refuse life-sustaining treatment, even if death becomes inevitable, whatever their motivation. But should the same respect for autonomy lead to a conclusion that there should be a legal right for patients to kill themselves?

Choice is not as simple as it sounds

As we saw at the beginning of the chapter, the author Terry Pratchett argued that everybody had the right to control the time and manner of their death. But this is not as simple as it sounds. Was Terry Pratchett really arguing that we should assist people to destroy their own lives under any circumstances and for any reason whatsoever? Would we wish to belong to a society that assisted suicidal people to kill themselves whenever they wished? Or to a society that provided humane methods for self-destruction, that made suicide an easy process for lonely, elderly, disabled or despairing people?

Of course, the Leadbeater Bill would not legalise assisting a suicide in any circumstances, even if the person had legal capacity. So, the principle of personal choice or autonomy is severely restricted by the proposed Bill, and those restrictions appear uncomfortably arbitrary. Why should an 18-year-old be able to exercise a choice to kill themselves but not a 17-year-old who was in an identical predicament? In other areas of English medical law it has been agreed that adolescents as young as 13 and 14 are capable of making autonomous decisions about their treatment without the agreement of their parents. Why should terminally- ill adolescents not be able to exercise their choice to kill themselves?

And why should I be able to exercise my settled choice to kill myself only if I have less than 6 months left to live, but not 9, 12 or 18 months. Why should the law restrict my personal autonomy in this arbitrary manner?

A settled and ‘uncoerced’ will to kill oneself

The rhetoric of choice and self-determination sounds compelling from the philosopher’s chair or the politician’s rousing speech. But in the complexities of human relationships and the play of tragic life circumstances, it is not so simple. Our choices, wishes and desires are all influenced by our societal context and by the web of relationships in which we find ourselves. Is it possible that my choice to end my life is being subtly influenced by the wishes of others?

A previous Commission into assisted suicide concluded that “...it is essential that any future system should contain safeguards designed to ensure, as much as possible, that any decision to seek an assisted suicide is a genuinely voluntary and autonomous choice, not influenced by another person’s wishes, or by constrained social circumstances, such as lack of access to adequate end of life care and support.”

But although this is clearly well-meaning, it is also frankly absurd. How can we ever be confident that a person’s choice to kill themself is not influenced by the wishes of others or by limitations in the social or medical support available? For example, in published reports from the US State of Oregon between 40 and 55% of those requesting medically-assisted suicide gave “Burden on family, friends/caregivers” as a reason.

It is common to find elderly people who are concerned that they are becoming an unwanted burden on their relatives and carers. Desiring to act responsibly and altruistically, they may come to perceive that it would be better for everybody if their life ended. And can we or others always detect the covert influences and emotional factors which lie behind our choices? In the words of Oxford Professor Nigel Biggar, the notion that we are all rational choosers is a flattering lie told us by people who want to sell us something. It is an uncomfortable truth that much of the time we are influenced and motivated by social and psychological forces that we barely understand. Baroness Onora O’Neill has warned that, “incorporating a few ‘safeguards’ into legislation cannot address the real difficulty of protecting patients against the consequences of choices which are not well-grounded.”

So, the burden falls on the attending doctor to ensure that there is no emotional pressure or coercion. But this seems to place unrealistic expectations on a busy professional who may only have a relatively superficial knowledge of the patient’s circumstances. It doesn’t take a genius to see how the system may fail to spot subtle forms of coercion, manipulation and emotional blackmail. The Bill proposes that a Code of Practice be set up to provide recommendations on best practice for doctors and administrators, but previous experience in the NHS shows that such regulations, although well-meaning, do not prevent egregious failures in practice.

Another common reason given for assisted suicide in Oregon is ‘fear of inability to care for self’. There have been well-documented cases in other countries in which worries about the lack of provision of high-quality palliative care have been a motivating factor for terminally ill patients to seek assisted suicide. If the Bill becomes law in England it seems likely that some vulnerable people will seek to end their lives because of glaring deficiencies in the social and medical support that is available. But is this something that we as a society should be facilitating by providing lethal drugs?

Although the proposed legislation states that no doctor is under any duty to raise the issues of assisted suicide (clause 4), in the highly regulated and litigious nature of medical care in the UK, once the Bill was enacted, it is likely that the process will become incorporated into standard medical care pathways. In due course it seems inevitable that assisted suicide would be added to the list of ‘treatment options’ which must be discussed with all patients across England and Wales whenever a terminal illness is diagnosed and made available universally, especially as the Health Secretary has the power to ensure that provision of assisted suicide becomes part of the health service in England and in Wales (clause 32) .

It is inevitable that legal cases will be undertaken against doctors who failed to inform patients that their life expectancy was less than 6 months and hence that they had the option of ending their own lives. To fail to inform patients about the option of suicide, even if the doctor thought it was inappropriate, would be deemed unacceptable and paternalistic.

But once the doctor raises the option of assisted suicide, how many vulnerable people might come to perceive the option to end their lives as a responsible course of action? In the current legal framework, as a terminally ill patient I do not need to justify my desire to continue living, however limited my life may become. But once ending my life becomes a ‘treatment option’, then I need to provide some reasonable justification for my desire to continue to live, particularly if I am worrying that I might be ‘a burden’ on my loved ones or NHS resources.

Matthew Parris, writing in The Times, agreed that legalisation of assisted suicide would lead to growing social and cultural pressure on the terminally ill “...to hasten their own deaths so as “not to be a burden” on others or themselves. I believe this will indeed come to pass. And I would welcome it...” As Parris put it, “Your time is up’ will never be an order, but — yes, the objectors are right — may one day be the kind of unspoken hint that everybody understands. And that’s a good thing.”

Mental Illness and Depression

It seems very likely that the great majority of terminally ill people who choose to kill themselves have at least some elements of what most of us would recognise as depression or persistently low mood. Clinical depression is common in terminal illness and suicidal thoughts are a cardinal symptom of depression. So is it possible for a terminally ill person with depression to make a rational choice to end their own life? Is the desire to end their own life based on a rational appraisal of their situation or is their perception being distorted because of mental illness? One psychologist who had studied people seeking medically assisted suicide in Oregon argued that the distinction was not clear, stating “...of the people who pursue this option, a sizable portion are rationally appraising their situation. And a sizable proportion are appraising it through a lens of depression.”

Some in favour of the legislation argue that depression shouldn’t necessarily make a person ineligible for physician-assisted suicide. In the normal course of life we don’t say that people lose autonomy to make decisions even if they become moderately depressed. Perhaps a degree of depression is a rational response to approaching death.

In summary, the apparently simple principle that people should be legally allowed to achieve their desire to end their lives turns out to be much more murky and complex than might at first seem.

This piece is an extract from John's paper, 'The Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill 2024: A Medical and Ethical Perspective'.

The full piece can be accessed on John's website at: www.johnwyatt.com/leadbeaterbill/