Someone once told me that my attendance at a pro-life protest meant that I wanted to hurt women.

The comment stung, not least because it came from someone I considered a friend, but because it so completely misrepresented what I believe.

After all, I am a woman, and I believe fervently in women's rights. At the time, I was very into feminism. I’d read the books, signed the petitions, joined the debates online. So to be told that my convictions made me anti-woman cut deeply.

Yes, I am pro-life because I recognise the personhood of babies in the womb. But that’s only part of it. I also believe, to my core, that abortion is profoundly harmful to women.

I know I’m not alone in that conviction—many Christians share this view. We care deeply about defending the most vulnerable, yet we also question a culture that insists women need abortion to be equal. And yet, we’re so often told that being pro-life means we hate women.

In a culture where abortion has become such a stronghold that Parliament barely flinched when it voted to allow abortion up to birth—all in the name of ‘protecting women’—we must respond.

Lovingly, but firmly, we must challenge the feminist assumption that abortion is a pro-woman position. To do that, we need to understand both the history of abortion and the consequences it has had for women and for society today.

Here are four reasons why this narrative must be questioned.

1. Abortion was not legalised for women’s empowerment

One might assume, given today’s pro-choice rhetoric, that abortion was legalised as part of a great feminist wave advocating bodily autonomy and self-determination. In reality, the story is far more complex.

Abortion played little part in the early women’s movement. It only became a prominent feminist cause in the 1970s when it was rebranded as the foundational right upon which other women’s rights depended.

Instead, abortion was legalised for two supposed public health crises. Firstly, there was the issue of backstreet abortions. Reports of thousands of women dying from unsafe, illegal abortions prompted Parliament to legalise the procedure in limited circumstances to address what was seen as a national tragedy.

Secondly, the thalidomide controversy—where hundreds of babies were born with disabilities caused by the prenatal drug thalidomide—galvinised public support for abortion. Alan Henry Clarke argues that this tragedy was viewed as the ‘turning point in public opinion and as the stimulus for real ‘professionalisation’ of the reform movement.”1

Amid widespread fear and misunderstanding about disability, lawmakers—echoing societal attitudes—saw it as compassionate or necessary to permit abortion where a child might be disabled. The 1967 Act therefore included a clause which might easily resemble eugenics: Ground E of the Act allows abortion on the grounds of foetal disability.

These attitudes betray the dark roots of eugenic ideology at the heart of the abortion reform movement. The group that lobbied hardest for this change, the Abortion Law Reform Association (ALRA), had strong ties with the Eugenics Society. According to academic Ann Farmer, ALRA members such as Dora Russell and Stella Browne viewed humanity as simply another link in the evolutionary chain. Those considered ‘unfit’ could therefore be eliminated to control population growth and preserve a supposedly superior race, with abortion and birth control central to that goal.2

They were influenced by prominent male eugenicists, including Havelock Ellis and Bertrand Russell. Ellis, a noted sexologist, maintained that women must have access to contraception and abortion to enable men to engage in unrestricted sexual relations for the sake of eugenic advancement.

It is interesting to note that moves to legalise abortion in the US also had roots in eugenics.

In her memoir, Subverted, former Cosmopolitan writer Sue Ellen Browder describes how the women’s movement was co-opted by the sexual revolution. She explains how figures like Larry Lader, founder of the National Abortion Rights Action League (NARAL), influenced feminist leaders and the landmark Roe v. Wade decision. Lader’s motivation, however, was not women’s liberation but population control—a concern rooted in eugenic thinking.

As Browder observes, the early women’s movement had focused on equal opportunity in education and work, while the sexual revolution prioritised sexual freedom. The two became intertwined—and largely for commercial reasons:

“Why was Cosmo so successful? Because it attracted advertisers. Why did it attract advertisers? Because it worked. When a young, insecure woman reads these magazines and thinks she needs perfume, cosmetics, hair products, beautiful clothes, singles travel… abortions, contraception—when she thinks she needs all these things, she’s going to spend a lot of money.”

This history may not convince everyone that abortion is unethical, but it provides vital context for understanding the legislative changes so often celebrated as landmark victories for women’s rights and the feminist movement. Far from being crafted for women’s liberation, the origins of abortion legislation sit uneasily with any claim that abortion is pro-woman.

2. Abortion is not ‘completely safe’ and can be harmful.

Another reason the pro-choice narrative falters is that it refuses to acknowledge the real physical and emotional harm many women experience after abortion. Too often, evidence of physical or psychological risks is dismissed or minimised.

Of course, honesty must go both ways. Pro-life advocates can also fall into exaggeration, suggesting that all women regret their abortions or live in constant pain.

Still, it is impossible to look honestly at the available evidence—both the scientific studies and the countless personal stories of regret, grief, and trauma—and conclude that abortion is always a harmless procedure.

Firstly, there are physical risks involved. For example, abortion has been linked to an increased risk of preterm birth in later pregnancies—a connection acknowledged by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG).

A 2013 review found a significant rise in preterm delivery among women with previous abortions, with risks up to twice as high for very early births. A Finnish study the same year reported a 28% higher risk of extremely preterm birth.

Then there are complication rates, particularly from medical abortion – now widespread thanks to the Pills-by-Post scheme. Evidence shows higher complication rates in medical abortions compared with surgical ones. The RCOG acknowledges a greater risk of bleeding and haemorrhage, and FDA trials found that 90% of women reported bleeding ‘much more severe’ than during a heavy period.

In a study of 42,600 Finnish women, Niinimäki et al. (2009) found serious complications were four times higher after medical abortions (20% vs. 5.6%), with haemorrhage rates of 15.6% compared to 2.1%. Follow-up research confirmed similar risks, and other studies show that about one in twenty women undergoing early medical abortion later requires surgical treatment for haemorrhage or retained fetal tissue.

Secondly, there are the psychological risks. Although these are fiercely debated, we can at least say that some women experience psychological harm from abortion. A 2011 review by the Academy of Royal Medical Colleges concluded that women with pre-existing mental health conditions were more likely to experience problems following abortion. A meta-analysis by Fergusson et al. (2013) found no evidence that abortion improved mental health outcomes, but some evidence of small to moderate increases in risk. Several longitudinal studies have reached similar conclusions.

Taken together, this evidence shows that abortion—especially medical abortion—is not risk-free, and women deserve full transparency about these potential complications to their physical and mental health.

To suggest, therefore, that anyone who raises concerns about abortion is ‘anti-woman’ is not only false, but dismissive of the very women whose voices deserve to be heard. Even when women express initial relief from abortion, studies and testimonies suggest that many later wrestle with complex emotions, often in silence because society insists they should feel only empowerment.

To pretend these harms do not exist is not empowerment—it is abandonment—and a movement that ignores women’s pain cannot call itself pro-woman.

3. Abortion has benefitted men more than women

Another reason the pro-choice narrative has betrayed women is that—far from levelling the playing field—abortion has largely freed men from responsibility, while placing heavier burdens on women.

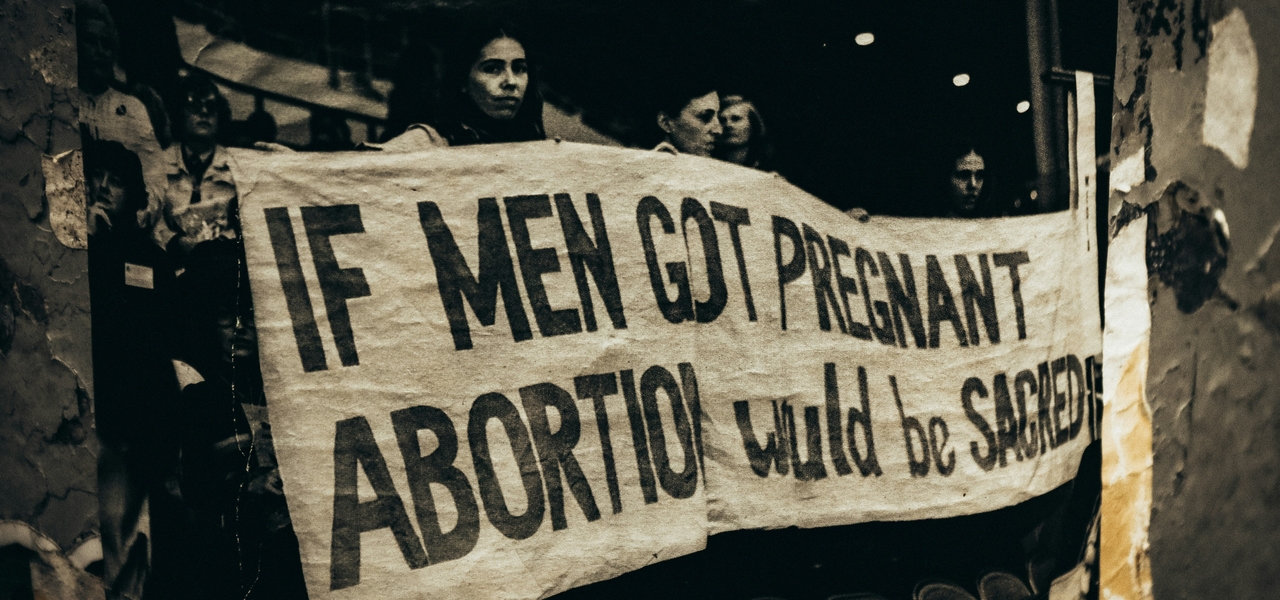

Feminists often claim that abortion is the key to women’s equality — that with the ‘choice’ of abortion, women are free to have sex without consequences, in the same way men can.

This has always been an argument I’ve struggled to comprehend. When it first gained momentum, society was in the midst of the sexual revolution and the era of ‘free love.’ Abortion offered women the freedom to engage in sex without the lasting consequences of pregnancy. Although the rise in contraceptive options, and the decline in traditional Christian sexual ethics, also played significant roles, abortion became the ultimate ‘get-out clause.’

Years later, it’s surely become apparent that this kind of ‘equality’ comes at women’s expense, not least because it’s men who want casual sex, not women. Yet it is women who carry the burden of said consequences: it is women who undergo the abortion, bear the physical and emotional toll, and carry the moral weight of the decision. And it’s women who are left to the exceptionally difficult task of raising a baby alone, if they decide to continue with the pregnancy. Not to mention how this has contributed to the social devastation caused by fatherlessness.

In practice, abortion has allowed men to enjoy all the supposed ‘freedom’ of the sexual revolution without its consequences. They can have sex without commitment or responsibility, knowing that the woman involved can deal with the pregnancy.

This is why a growing number of feminists, particularly in the United States, challenge abortion as a patriarchal tool rather than a liberation. Secular groups like Feminists for Life argue that abortion enables male irresponsibility and perpetuates, rather than dismantles, the oppression of women. We need more of these groups here in the UK.

Indeed, this is something that concerned early feminists in America. The earliest feminists in the 19th Century did not endorse abortion. They “feared that separating intercourse from reproduction would facilitate male infidelity, destabilizing marital relationships on which women were enormously dependent.”

And isn’t that what we see today? While it’s a good thing that women are no longer entirely dependent on men, our culture bears the scars of the sexual revolution and subsequent fracturing of the family structure.

And it’s women who pay the price. As journalist Louise Perry highlights, studies consistently show that following hook-ups, ‘women are more likely than men to experience regret, low self-esteem and mental distress.’

Then there’s the issue of sexually transmitted disease. 2023 alone saw over 400,000 new STI diagnoses in England, and young women under 25 accessed sexual health services at more than 100 per 1,000. Finally, the increase in casual sex has increased rates of unwanted and harmful behaviours during sex; one survey found that 77.8% of unwanted sex occurred in the context of hookups.

Casual sex and abortion have become so widespread that they have contributed to a profound devaluing of unborn human life—so much so that abortion is now often treated as just another form of contraception.

It is a tragedy that, even with the ability to look back on the devastating cost of this cataclysmic change to society, many feminists still believe women benefit the most from abortion.

4. Abortion has distorted the beauty of motherhood

Perhaps one of the saddest consequences of the feminist pro-abortion mindset is the way it has devalued motherhood.

The abortion debate goes far beyond the idea of sex without consequences. For many feminists, the core issue is the belief that women must be able to avoid motherhood in order to be equal to men and to protect their so-called ‘bodily autonomy’. Regardless of the humanity of the baby, women get to choose if they want to be a mother. While some deny fetal personhood altogether, others—including prominent feminists like Ann Furedi—accept personhood but still maintain that the mother’s choice must take priority.

I am not against the concept of choosing motherhood, but why can’t that choice end with contraception? Why does it have to involve women intentionally ending the life of their unborn baby? Is that really what empowering women looks like? As one Gen Z pro-life advocate bluntly put it, “I don’t think equality for women looks like dead children.”

Pitting a mother’s rights against her baby in this way is deeply wrong. Over time, this rhetoric has encouraged people to describe their abortion as “getting rid of a parasite.” Even Ann Furedi, former CEO of BPAS and one of Britain’s leading defenders of abortion rights, has expressed concern about this hardening of attitudes:

“And one of the things that I think is a problem, although many of my colleagues wouldn't, is the changes that have been made have led to a casualisation of the notion of human life...’

This attitude has its roots in the early abortion movement, who often viewed motherhood with deep ambivalence. For instance, Stella Browne, one of the movement’s most prominent voices, once said

“I have no experience of maternity, nor of the desire for maternity, which is generally attributed to women. Also I think much actual motherhood is unwilling, and this is an irremediable wrong to the Mother and the Child alike.”

Of course, Browne may have been reacting against entrenched Victorian attitudes which viewed women as nothing more than property. Yet by rejecting motherhood altogether, she also rejected the profound good that motherhood brings. Sadly, her view still echoes today.

While abortion rates are rising among women over 35 (many of whom are already mothers), the highest rates are among women in their early twenties. For many young women, the prospect of motherhood is unappealing, or downright terrifying.

And I do have some sympathy with that view since I became a mum myself. Entering motherhood at 37 meant I’d enjoyed years of relative freedom. Experiencing this rapidly dissipate the moment my daughter was born, shocked me. This little person was demanding everything of me and I would never be able to get my old life back. Over the coming months, the sheer grind of motherhood was relentless. I missed work, I missed friends, I missed quiet, and—most of all—I missed sleep.

And yet, it’s impossible to describe how much the sacrifice is all worth it. Our culture needs to understand that just because something is hard, that does not mean it is bad for us. As Christians, we believe in the innate goodness of having children. Psalm 127: 3 describes children as an abundant blessing: “Behold, children are a heritage from the LORD, the fruit of the womb a reward.” I now have the joy of knowing this to be true. The tremendous love you feel for your child eclipses everything . Even amongst the tantrums and mess there are moments of joy that permeate your days, and seeing your child discover life and develop their little personality is the greatest gift. I wish I could help women in unplanned pregnancies see there is so much hope in their situation, so much joy and fulfilment ahead.

But this devaluing of motherhood has had wider societal consequences—where mothers and families were at the heart of social policies, there is now a shocking lack of support for mums. Maternity pay is just one pitiful example—mums earn less than the minimum wage while on maternity leave, and that’s if you’re even lucky enough to qualify.

I saw this injustice up close through a local single mum I befriended on maternity leave. After her marriage broke down, she lived in a single rented room with her baby, with no family nearby. The council told her she wasn’t enough of a priority for housing, and childcare costs made returning to work nearly impossible. She often confided that she felt she was failing her child—but she was being failed by a system that makes motherhood an uphill battle.

Is this how we’re content to treat mums in our society? We’re happy to fund hundreds of thousands of abortions every year, but mums are barely able to make ends meet?

In a culture where abortion is seen as a viable and even necessary option at times, there’s little incentive to fix a system that punishes women for choosing motherhood. Instead of improving maternity pay, childcare, and community support, Parliament has chosen to decriminalise abortion up to birth. That choice speaks volumes about our national priorities.

To put it plainly, if feminism is about empowering women’s choices, then it needs to empower mums too.

Putting ourselves in their shoes

Sometimes I think it’s good to put ourselves in the shoes of those who disagree with us. To ask, ‘But for the grace of God, would I be pro-abortion too?’

I like to think I wouldn’t be, because I think there are plenty of secular arguments that support the pro-life view.

However, the message of equality and autonomy is so powerful that I don’t doubt I would be swimming along with the cultural tide.

And I don’t think the church and pro-life movement has always helped. Sometimes it feels like our dominant position has either been silence about abortion, or a dominant focus on promoting the humanity of the unborn baby.

This has given credibility to the argument—often made by abortion advocates—that the unborn baby is all we care about, and the pregnant woman is irrelevant, merely a vessel to carry a precious human being.

If we truly believe that both mother and child are made in God’s image, then our response must be radical compassion for women that is also deeply practical. We must build communities and advocate for policies to support women to choose life. The church must be a home for struggling families, and come alongside single mums. We must pray for drastic cultural change around sexual ethics and motherhood.

And we must also continue to speak out boldly about abortion. Our culture has believed the powerful lie that abortion is, at worst, a necessary evil and, at best, a moral good. But love tells the truth, even when it’s costly. And if we speak that truth with grace and courage, alongside showing practical care, perhaps we can help our world rediscover what it truly means to be for women — and for life.